By Dr Harriet Allsopp

On 23 April 2024, the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Act was passed. By writing into law that the Republic of Rwanda was a safe third country, it gave legal provisions for the deportation to the African state of people seeking asylum in the UK. The Act and the UK-Rwanda treaty that it supports have taken the UK’s “hostile environment” policy a dangerous step further than other deals that offshore asylum processing. By transferring both asylum claims and refuge, even successful asylum seekers will not return to the UK where they sought asylum but will only be eligible to stay as refugees in Rwanda.

It is, in effect, “the wholesale transfer of the UK’s asylum responsibility to another country”. With several substantial legal challenges and new evidence stacked up in the courts and a general election on the horizon, the agreement may never come into effect. Nevertheless, it sets a precedent for future deterrence agreements across Europe to eschew legal responsibilities to protect and to reinforce colonial logics of bordering and hierarchies of worth and vulnerability.

An increasingly hostile environment

Legal routes for entry to the UK for the world’s most precarious, at risk and vulnerable people, and avenues to apply for asylum have steadily been narrowed and reduced, most recently by the controversial Nationality and Borders Act 2022 and the Illegal Immigration Act of 2023.

Together the acts criminalise asylum seekers arriving via “irregular” routes (such as small boat), disqualify them from being eligible to apply for protection on the UK, and create the provisions for them to be removed to third countries for asylum processing. With most countries of origin deemed unsafe for repatriation, the majority are stranded in permanent limbo within the UK, having had their asylum claims declared permanently inadmissible, but not removed (Refugee Council).

Research on offshore processing suggests that removals to Rwanda will have detrimental effects on mental and public health (Parker and Cornell 2024; Chaloner et al. 2022; Smith et al. 2023; Boeyink 2023). Already traumatised people are criminalised, detained and dehumanised. They are rendered, in the words of Mbembe, discounted bodies – bodies at the limits of life. For asylum seekers in the UK, the spectre of the Act has already forced thousands of people, most having fled conflict, persecution and climate change and having experience multiple traumas enroute to the UK into situations of extreme precarity and vulnerability.

A week after the Safety of Rwanda Act passed into law, the Home Office confirmed that, under “Operation Vector”, people whose asylum claims had been refused were being detained, through raids on homes and hotel accommodation across the UK, and when reporting in. Scores were handcuffed and transported in police vans, leaving any worldly possessions behind, and held in detention centres awaiting enforced deportation. After the government conceded that no flights would depart before the General Election in July, dozens were released on bail, but remained subject to future removal. Thousands of others, already on the limits, debilitated and deprived of protection, were reported to be unlocatable.

Although the Rwanda Act limits what kind of legal challenges can be presented to the courts, they have already appeared from diverse directions: from senior civil servants on the grounds that implementing it will force them to act illegally, to ignore interim ruling of the European Court of Human Rights, producing an unlawful conflict of interest, to charities supporting and safeguard asylum seekers. Meanwhile, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, called on the UK Government to reconsider the bill because it “erodes” legal frameworks for protection. Indeed the “bill poses the most serious of challenges to the role of the courts, human rights protection under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECTH), the separation of powers and the rule of law” (Birkinshaw 2024).

The view from Rwanda and the wider context

The UK is said to have juggled with several possibilities for the deal: Iraq, Ascension Island in the South Atlantic Ocean, Albania and Ghana, as well as Gibraltar and the Isle of Wight. In April, The Times and the The Daily Mail reported that leaked FCO documents suggested the government had shortlisted several other countries for future deals: Armenia, Ivory Coast, Costa Rica and Botswana, Eritrea and Ethiopia. Aside from Rwanda, however, no third country had agreed to accept asylum seekers from the UK in large numbers. The UK-Rwanda Migration and Economic Development Partnership of 2022 was born.

One of the most densely populated countries in Africa, Rwanda has high unemployment, is the most unequal country in the East Africa region and, in 2021 had 48.8 percent of the population described as multidimensionally poor. Affordable housing is in short supply, and 60 percent of the population lives in informal settlements. Rwanda is still rebuilding following the genocide of 1994 and is focused on economic development and global positioning. It already hosts a large number of refugees, (the majority from Barundi, Congo, and those removed by the UN from Libya since 2019,) accommodated in six open camps across the country, and it is said to have a progressive stance towards refugees . By its neighbours and by Rwandan opposition figures, however, the government is accused of complicity in M23 military incursions in Eastern Congo. They condemn the deal with the UK, arguing that it endorses the suppression and persecution of dissent and fuels the conflict that has already resulted in thousands of deaths and caused millions to be displaced.

The Rwanda Bill follows a wealth of UK and EU legislation and international agreements, exploiting emergency rhetoric that accompanied the 2015 “migration crisis”. All externalise asylum commitments, migrant presence, processing and containment, blocking and interrupting the passage of racialised migrants at the borders of Europe or further afield. All are tied to economic incentive. Payments to cover asylum processing and operational costs within the Rwanda deal are complimented by an economic development package (the Economic Transformation and Integration Fund, ETIF), designed to support economic growth in Rwanda – a country attempting to redefine itself from a “failed state” into “the ‘Singapore’ of Africa”.

Such migration agreements have become a new territory for international agreements, offering financial and political incentive tied to migrant management and thwarting mobility and granting European states further influence over former, or new, colonies. It is a new international development agenda in which economic power has emerged as a “shield against new arrivals” (Morano-Foadi and Malena 2023).

An enactment of necropolitics

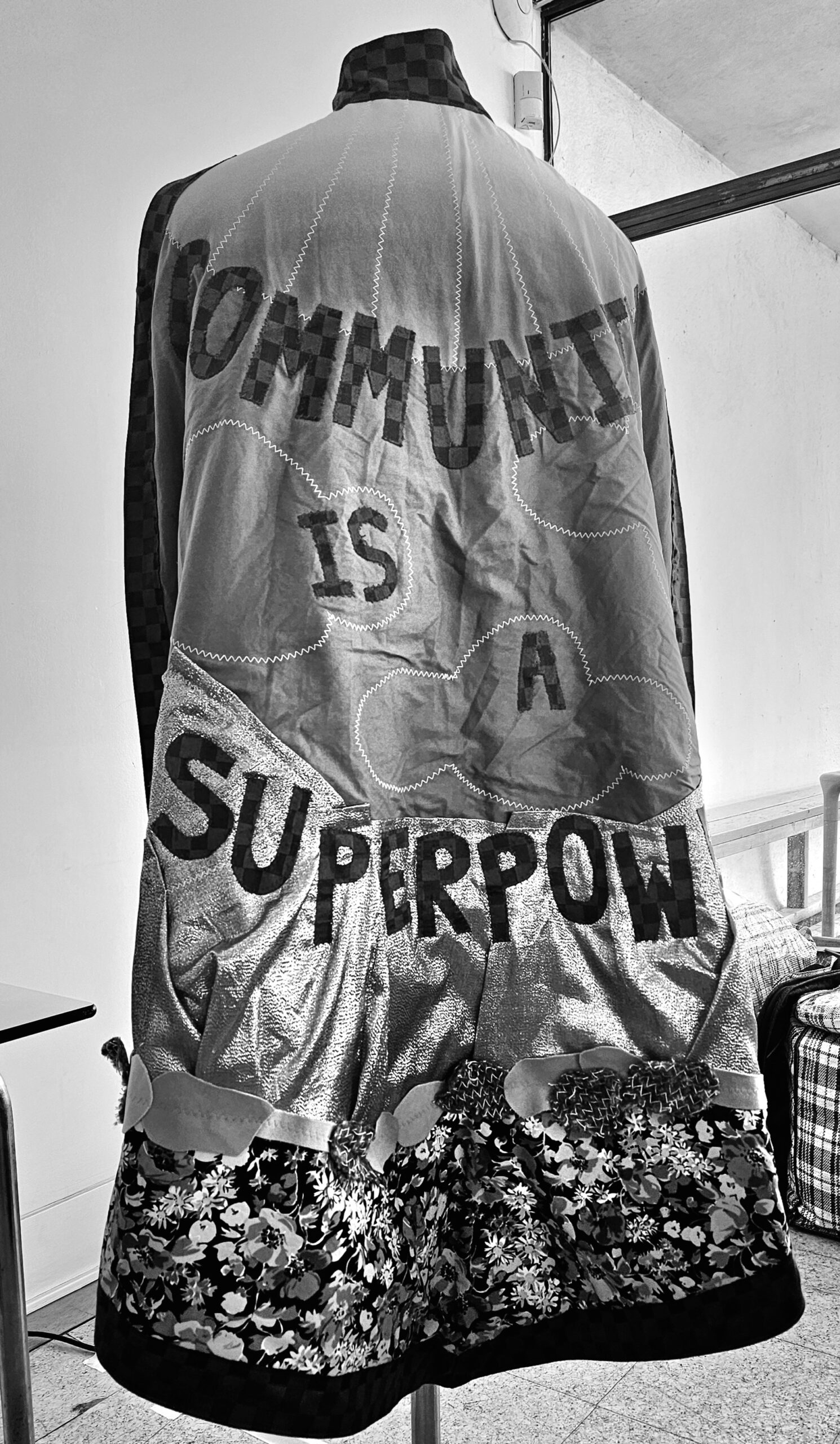

The UK’s Safety of Rwanda Act and Immigration and Borders Act have been described as an “enactment of exclusive colonial b/ordering regime” creating differentiated bodies at the limits of life (Phipps and Yohannes 2022). They are part of broader attempts of western countries to strengthen, close and externalise their borders, and to control the movement of people – a redefinition of territorial boundaries (Morano-Foadi and Malena 2023).Through such bordering, migration and migrant bodies become spaces of exception, of extra legality, outside the realms of protection (Phipps and Yohannes 2022). The detention and forced transfer of asylum seekers from the UK, from the borders of Europe to Africa, to remote locations, a perverse reenactment of human trafficking that, paradoxically, sits at the centre of justification for these brutal border regimes and agreements with countries along migration routes, and justified through colonial logics.

Detaining and containing, criminalising and invisibilising people on the move in isolated mass accommodation, offshore on barges, in detention on the borders of Europe and forcibly transferred beyond them to countries such as Rwanda are acts of racial differentiation and colonial violence, with echoes of colonial population transfers and the slave trade. Devalued, deviant migrants become “cheapened, super exploited and disposable” labour (Rajaram 2024; Mezzadra 2011). As Gurminder Bhambra and Laura Basu remind us, the borders erected by through “decolonisation” and claiming sovereignty, “were actually acts of re-colonisation, blocking those who built Europe from accessing its wealth”. Today, the Rwanda deal, along with other acts of enforcing the borders of Europe, and offshoring asylum, should also be understood as acts of re-colonisation, or continuing coloniality. The transfer of asylum seekers, the wholesale outsourcing of asylum and refuge, is a contemporary colonial practice of moving people against their will, in order to further the goals of wealthier nations.

Feeding on emergency and crisis rhetoric, the threat of “criminal hoards breaking in” to western states but drawing on colonial legacies and continuing colonial practices and knowledge, these migration policies are imbued with racialised hierarchies that normalise the removal of rights from black and brown bodies. It is ultimately a “politics of non-lethal violence: the strategic and attenuated delivery of injury, maiming, and incapacitation that shapes contemporary borders” (Davies et al. 2024:1; Paur 2017).

The crisis narrative, whether focused on the numbers involved, the challenge of housing, the risk of journeys, the people smugglers, frames migration as an exceptional managerial problem that can be addressed through criminalisation, expulsion and the expansion of securitised detention. This aggressive inhospitality, epitomised by the Rwanda Act, undermines human rights, prevents migrants’ access to life sustaining infrastructures, inflicts slow violence (Nixon 2011), debilitation (Puar 2017) and ultimately slow death (Berlant 2007). It calls upon a thinly veiled cruel colonial logic that differentiates between lives worth protecting and saving, and others that are not. The Rwanda Act manifests a “necropolitical experimentation” in “uninhabitability and inhospitality” (Phipps and Yohannes 2022), that removes refuge itself from UK soil and is designed to render migrants continually displaceable yet immobile, precarious and disposable, debilitated and “let die” offshore, beyond the fringes of Europe.