Attention, this scam – now known as “CEO fraud” – is currently on the rise again!

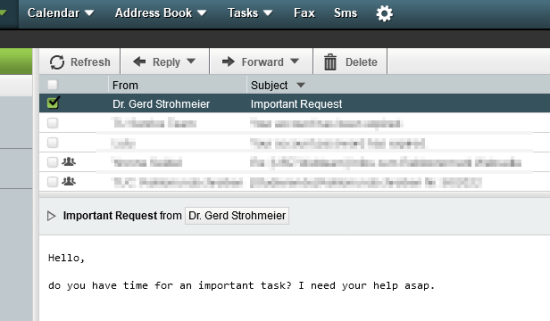

If you get a short e-mail from your supervisor, you generally react quickly, don’t you? What would you do if you received this e-mail?

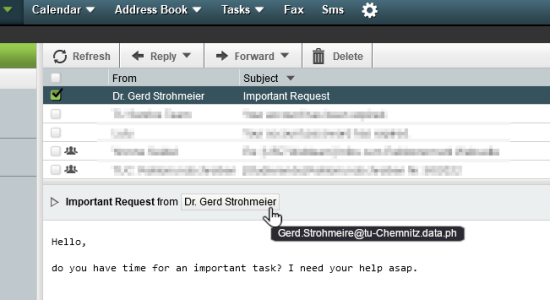

If you look closely at this e-mail, you will notice that the sender’s e-mail address is an external address that you probably have never heard of. (In some e-mail programs, you have to hoover over or click on the sender’s name to show the e-mail address).

You are not used to such spelling mistakes from the president. This will make you wonder, so that you will inquire on the usual channel (by call, by known e-mail address) and not answer this dubious e-mail.

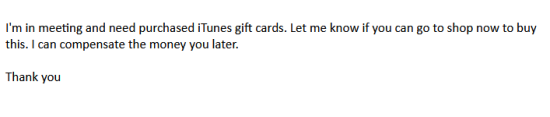

However, in the often hectic working day, your first reaction after a glimpse may be different: You answer quickly. Then you might receive such a reply:

The poor English here betrays the attempted scam. In another example, the address was in good English – this was about Amazon vouchers. Ultimately, the sender wants you to spend money and then send him the voucher code. The scam here is based on the simple trick that the name in the sender’s address (which is not in <…>) is freely selectable in many email programs. Then the fraudster sends short e-mails to recipients who are related to the fake name of the sender. However, the entire sender address can also be forged and is not trustworthy.

How does the fraudster proceed?

You may ask yourself how a fraudster actually knows which persons are in an official relationship so that his request appears credible and has a chance of success. We can only guess: On many websites, this information is publicly visible. Although the e-mail addresses are disguised, they can be determined with effort.

This principle is called social engineering: by knowing the social environment and pretending to have an identity, a victim is to be provoked into activities. Contact can be made by telephone or – easier and more effective for the fraudster – electronic communication. Besides fraud, it can also be about gaining confidential data. There is nothing new to this information (the film “Catch me if you can” about the con man Frank Abagnale is recommended), but in the current electronic age it is probably very profitable without having to put in a lot of effort. “Phishing” is a similar phenomenon: fake emails that pressure recipients into revealing their access data.

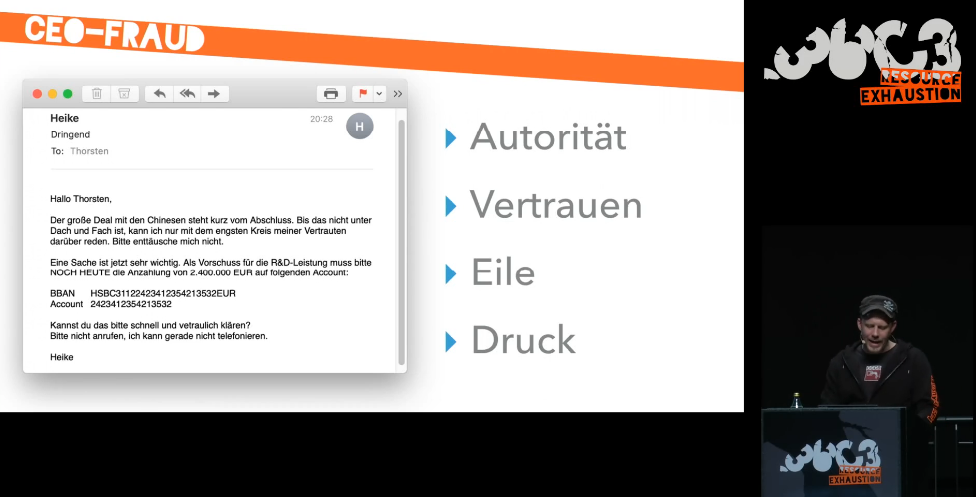

Psychological background

But how is it that we make certain decisions in our routine everyday life that would turn out quite differently with a little distance and calm? The reason probably lies in psychology. The psychologist, IT security consultant and spokesman of the Chaos Computer Club Linus Neumann showed in his recommendable lecture “Hacking Brains – Human Factors in IT Security” at the 36c3 that our brain has two working modes, so to speak: System 1 works quickly, intuitively and automatically and is used in fear and routine situations. Under stress, we therefore click on links or answer e-mails quasi automatically, which we would never do in the rationally controlled working mode 2 (analytical, considered) in the case of such an e-mail. So these scammers will always try to catch us in mode 1. That’s why they prefer to receive such e-mails on Friday afternoons or before public holidays.

To avoid these risks, the question arises as to how we can succeed in electronic communication to get into rational mode 2, i.e. without fear, stress and routine. This is a question that probably cannot be solved technically. Can our psychologists help here? Our only advice is to keep tabs on your e-mails!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.